Monte Carlo Integration

Motivation

Quadrature rules

To integrate the function \(I = \int_{\Omega}{f(x) dx}\), where \(\Omega\) is the domain of integration. If \(f(x)\) known to you and can be evaluated analytically, then you are good. But usually that's not the case, \(f(x)\) behaves like a blackbox (you give it an input and it spits out an output), it needs to be integrated numerically.

Pretend you don't know the equation for the following function and you want to know its area bounded by it. In high school, we were taught that the integral can be approximated with infinitesimal rectangles, a.k.a. the rectangle rules. So let's put together a bunch of rectangles and crunch some numbers!

As the number of rectangles grows, the closer it fills the target area. To which I can say with confidence the area is \(\pi/4\) since it's obviously a quarter of a circle.

There are more similar approaches to do integration and they are known as quatrature rules. The generalized form looks like this \(\hat{I} = \sum_{i=1}^n w_i\ f(x_i)\). The weight \(w_i\) is defined differently in other rules, e.g. Midpoint rule, Trapezoid rule, Simpson's rule, etc.

Downside

These kind of numerical approximations suffers from two major problems.

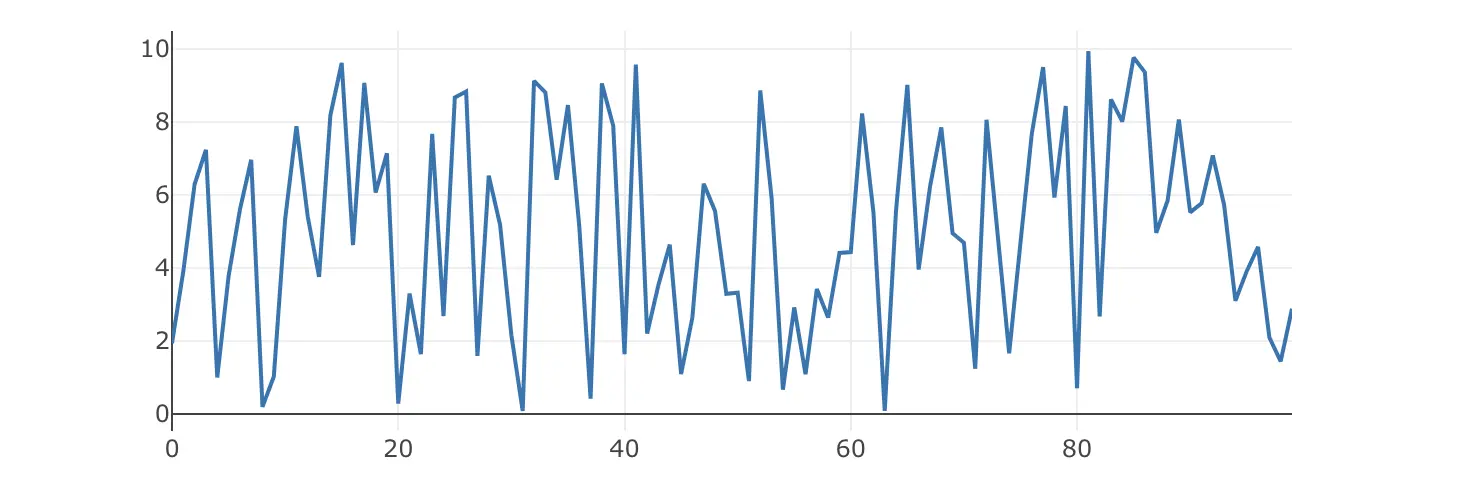

High-frequency signals

Graphs like this can't be easily approximated with thick bars. To get closer to the real value, the bars must be really narrow which means more iterations to compute.

Graphs like this can't be easily approximated with thick bars. To get closer to the real value, the bars must be really narrow which means more iterations to compute.

High-dimensional domains

where \(s\) is the dimension, \(w_i\) is the weights and \(x_i\) is the sample position in the domain. Which is always the case when solving light transport problems.

Definition

As the name suggests, we can integrate functions with stochastic approaches through random sampling. With the Monte Carlo method, we can tap into the power of integrating arbitrary multi-dimensional functions!

where \(p(X_i)\) is the probability density function (pdf). And we can verify that with sufficient samples, it will eventually converge to the expected value \(I\).

It comes with the following benefits:

- It has a convergence rate of \(O(\frac{1}{\sqrt{N}})\) in any number of dimensions, which quadrature rule methods cannot achieve.

- Simplicity. All you need is two functions

sample()andeval(), and occationally finding a suitable pdf.

Sampling random variables

Generating uniform samples (e.g. \(p(x)\) is a constant) gurantees convergence but its rate is much slower. Ultimately, the samples should be drawn from a specific distribution such that most contribution to the integral is being extracted quickly from the domain. In other words, sampling carefully reduces the time to compute the ground-truth result.

Inverse Transform Sampling

This is a method for generating random variables from a given probability distribution (pdf) by using its inverse cumulative distribution (cdf). Imagine the likelihood of picking a random variable \(X\) follows a normal distribution, and we want the samples to be drawn proportional to its likeliness. A cdf table is built by summing up the marginal distributions (It's totally fine that the pdf doesn't add up to 1, since the sample will be drawn from the range of cdf which can be normalized by its maximum value). Then uniform samples \(U\) are drawn in the inverse domain of cdf such that random variable \(X\) is picked with \(X = cdf^{-1}(U)\).

From the above example, we can see most samples are centered at the highest probability area while the tails on both sides will have lower sample count. Good thing with this method is that it can be easily extended to multi-dimensional cases, and stratifying samples in the domain helps improves exploring the entire domain.

Downside

The pdf must be known, also building the cdf takes time and memory. And if the cdf cannot be inverted analytically, numerically computing the inverse mapping value (e.g. binary search) on every drawn samples is quite costly.

Note: A more efficient sampling structure exists out there, and it's called the Alias Method, which samples can be drawn in constant \(O(1)\) time. // TODO: Make a page about this

Rejection Sampling

When the pdf is difficult to sample, we can instead sample from a simpler density \(q\) such that \(p(x) \le M q(x)\), where \(M\) is a scaling constant. For instance, you want to integrate the area of an arbitrary shape but directly sampling the shape is hard. However, you know it's much easiler to draw samples from a box. So let's throw some dots onto our sample space!

The sampling space is defined as the tight bounding box of the shape, since drawing samples from a square is much simpler. We know the probability \(p\) of picking a sample point inside the shape is always less than the density \(q\) (it's completely enclosed within the bound), it's eligible to use this strategy to draw a sample. To draw one:

- Sample \(X_i\) according to \(q\) (draw a point inside the square)

- Sample \(U_i\) uniformly on \([0, 1]\)

- If \(U_i \le p(X_i) / (Mq(X_i))\), return the sample \(X_i\)

- Else, repeat 1

In the above case, \(p(X_i)\) is \(\frac{1}{area}\) when the point is drawn inside the shape else zero, and \(q(X_i)\) is always \(\frac{1}{64}\) because we are uniformly sampling a 8x8 square. Given that \(U_i\) has a trivial probability of being 0, we can safely assume that all valid samples \(X_i\) are located inside the shape. Thus we know they are good samples.

Importance Sampling

\(N=\) \(\int{f(x)}dx =\) Approx \(=\)

BSDF Sampling

Depending on the surface properties, there are certain directions (\(w_i'\)) the BSDF favors after an interaction. To get the more contribution from the function, samples have to be drawn proportional to the \(f_s\)'s shape. Because BSDF samples are drawn inside the solid angle domain, the probability \(p(w_i')\) is also measured in solid angle.

Light Sampling

In case when BSDF failed to find a significant contribution, other words the outgoing ray direction missed the light source, light sampling then comes into play to provide as a backup strategy.

\(G(\mathbf{x}\leftrightarrow\mathbf{x}')\) often refers as the geometric term, which was introduced because of change of variables. When changing from projected solid angle \(d\sigma^\bot(w_i')\) to area measure \(dA(\mathbf{x})\), it is required to have this term to normalize the integral:

To importance sample the light instead of solid angle, the density \(p(\mathbf{x})\) is predetermined since it is just the probability of picking a point on the manifold surface, i.e. \(p(\mathbf{x})=\frac{1}{Area}\).

Transformation of Space / Conversion of Domain

Multiple Importance Sampling

Next event estimation can be seen as a multiple importance sampling1 approach of integrating the radiance since it combines two sampling strategies, BSDF sampling and light sampling, often called as direct and indirect lighting.

-

Veach, E. (1997). Robust Monte Carlo Methods for Light Transport Simulation. (Doctoral dissertation, Stanford University). ↩